I’ve been told I have a high tolerance for chaos. Maybe that’s why March Madness hits just right in my world. That, and I am a hoops junkie from way back, because Indiana.

I’m still trying to adjust my planning to an A/B block schedule. I know that any one day is the equivalent of two, but there are still some hands-on discovery type of activities that I’m willing to sacrifice for. Plus, we had just quizzed on the Monday before spring break, and with two blocks for each of my Red and Grey day classes, starting a new half-unit that I’d just have to re-teach in 10 or 12 days didn’t seem like my best move. I had an Amnesty Day scheduled for the final block before break so I just needed something for Tuesday/Wednesday.

The Tuesday/Wednesday before the greatest two days in sports.

March Madness.

I’ve done this activity during (or close enough to) the probability unit in Algebra II for a few years now. It was a little out of sequence in my geometry class this year, but after 18 months of remote/hybrid learning I could justify it as a way to review some linear concepts and probability as well.

Basic story is, I have my students make a tourney bracket strictly by coin flip. My kids who know hoops always laugh when they have two 16 seeds winning in the first round or a double-digit seed winning the whole thing. That of course is part of the hook.

Then I point them to the Washington Post’s NCAA Tourney app where they research the first-round win percentage for each of the 16 seeds. (Hint: it’s somewhat linear).

Then I direct them to a Desmos graph I set up for them to fill in a table with their findings. Then they use sliders to try to make a line of best fit for the data.

I follow up with DePaul University professor Jeff Bergen breaking down the math behind picking winners, and the numbers that work against the likelihood of a perfect bracket.

Now they see there is some benefit to using strategy to picking winners, even if they don’t know the game it’s gotta turn out better than a 50-50 chance for each game.

So they make a “for real this time” bracket with their new-found knowledge. Among the reflection questions I ask them is to predict how much better they will do compared to their coin-flip bracket. I hold on to all the brackets and track their progress through the tournament.

Allowing for my 80-minute time limit I had to condense the project a little this year, but here’s the slide deck for 2022.

Now when a 15-seed makes the Sweet Sixteen and I drop that knowledge on them during a bellringer, we’re speaking the same language.

So, that Amnesty Day we were talking about up near the top of this post? The geometry team decided from jump that if quizzes would be 70% of the overall grade (by school policy) then we would offer our students retakes on any quiz (up to three attempts) and we keep only the highest score. It takes a lot of pressure off and keeps kids in the game who otherwise might check out when they see their grade nosedive.

Originally the plan was to offer the retakes after school, but we quickly found that after school does not work for a lot of our students. So we decided as a group to build in “makeup days” where students could do the retakes/corrections or turn in late work during their regular classtime. I also build in a small extra credit opportunity on our Amnesty Day. And it’s been paying off in terms of results.

I’m not sure I’ve ever had a class average 80% for a quarter before. I think that’s what the TFA people would call “significant gains”. They’ve earned it tho, by going back and re-learning and re-testing. Is there some answer-sharing going on when kids are taking quizzes over and over, at different times? Absolutely. But I’d bet no more than in a one-and-done quizzing scenario where the stakes are much higher. And do I still have students check out? Oh for real. See those averages in the 40s? Those classes have a half-dozen or so kids each with like a 5% for the semester. I have airballed all my attempts to motivate them.

All this has me thinking about real human stuff. When we build in second chances, my students don’t see me as an enemy to be conquered but a partner in their school journey. I think that more than anything has to do with their success. The mindset comes first, the improvement follows.

When a student comes in after school to see if I’ve graded his re-take yet, finds out he overshot his target by a whole letter grade, then shakes my hand and says,”Thank you”…. whoooo.

We’re doing something right. Both of us.

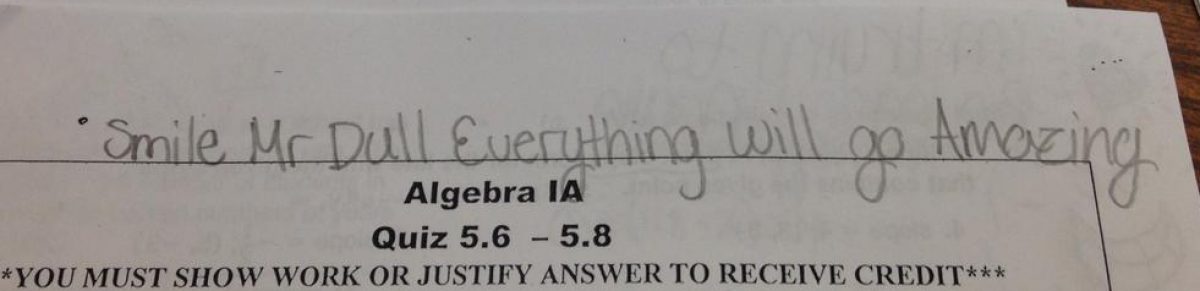

Then there’s the email I got from a student on Thursday night:

Being creative in the classroom, connecting with students, sharing their joys and frustrations on the daily, helping them learn math, it’s what I do. And it’s re-energizing me for the final quarter.

Also: it’s hard to not love this from St. Peter’s head coach Shaheen Holloway.

My Region people felt that.

As hard as it would have been to believe at the start of the year (so much everything), there’s joy back in teaching again. Like the newest darling of Cubs Twitter says, when that’s gone, I’m gone.

Spring Break is here. I brought my kids in for a safe landing at the end of the third quarter. Got some quizzes to grade and quarter grades to post, but it’s also going to be 70F here tomorrow and that seems like a good excuse to put air in my bike tires and go for a long ride. And my youngest wants to go see Bulls-Raptors at the UC and I think we can do that too. Walk my dogs. There’ll be plenty of rainy crappy days to stay inside and do school stuff this week.

I like chaos as much as the next guy. Maybe more. But I also appreciate the time for peace and rest and recharging. Happy Spring Break, teacher friends.