I’m a veteran of the Mental Game of Summer. Those first two weeks of June after school lets out are mine. To sit in the sun with a cold drink, wipe the hard drive clean, reminisce, forget, curse, ponder, recover. The last two weeks of June are filled with all the possibilities of play you can imagine. Carefree. Just gonna sit in the backyard and read? Sure. Sleep 11 hours on back-to-back nights? Zzzz. Impromptu road trip? Let’s Go.

The Fourth of July, America’s great national celebration of independence, is the fulcrum. The day itself is joyful. But the night brings the first hint of the Sunday Night Blues, like a chill wind on an August evening.

When I wake up on July 5, next school year is practically here.

This year the anticipation (dread?) is rearing its ugly head early. Mostly due to rampant uncertainty over what the start of school will look like in the midst of a global pandemic.

The plans, or at least a multiple-choice question involving possible plans, will start trickling out of the next few days. Governors in Texas and Michigan have both announced that school will re-open for in-person instruction.

Elsewhere:

In my district this week the interim superintendent presented details of a community survey that shows parents overwhelmingly favor face-to-face instruction when school opens in 8 weeks. No decision about re-opening school has been announced yet. And even an announcement (from a different district) that students will return to the classroom doesn’t necessarily mean seven hours a day, five days a week.

I felt like I managed the transition to emergency distance learning pretty well in the spring. But if everything I do starting in August is going to have to be convertible, and accessible to both in-person and distance learners, that planning needs to start like yesterday. Most of the wise people I follow have recommended building the online course first, then pivoting to in-person as needed since that’s an easier transition than the opposite direction. (Lengthy twitter thread opened by John Stevens here). I’m down with that.

Regardless of the setting, my main goal for the new year is to intentionally build in retrieval practice as outlined in Powerful Teaching by Pooja Agarwal and Patrice Bain. I’ve been slowly working my way through the text since February, and have been introducing some of the concepts all year. (Info and resources here, but you really sould read the book).

The authors have worked together to research and implement cognitive science, and now have teamed up to package their findings into Powerful Learning.

They refer to the four basic building blocks as “Power Tools”, and you might find that they sound famliar from your practice, even if you used a different name. I did, for sure.

- Retrieval Practice: as the authors put it, “pulling information out of students’ heads rather than putting information in students’ heads”.

- Spaced Practice: the opposite of cramming, spreading recall opportunities out over time.

- Interleaving: mixing closely related topics so students have to differentiate between concepts.

- Feedback-driven Metacognition: “providing students the opportunity to know what they know and know what they don’t know.”

So a 3-2-1 summary after a notes video, or a rousing game of “The Fast And The Curious” or a warm-up that spirals back to last week’s topic or a “Green Sheet” that students use to prepare for a test or a review package that jumbles the order of topics, all qualify.

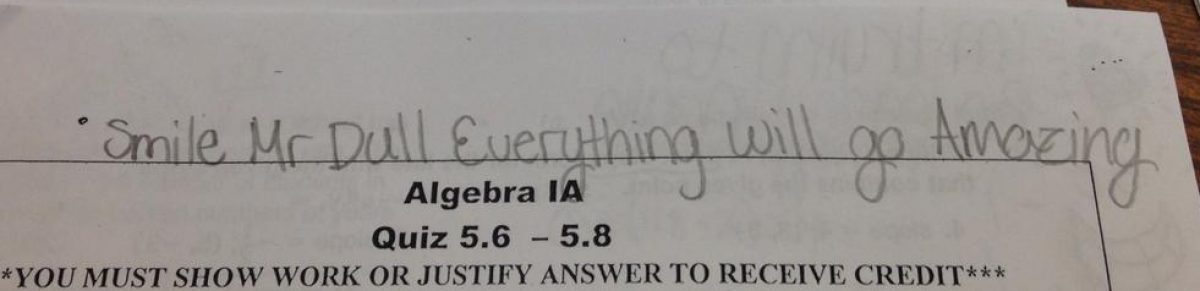

Patrice Bain talks about asking her students to have a “pointless conversation”. That’s a little unnerving to kids who have grown used to churning out squiggles on a worksheet. But I built some “check-in/no-right-answer” questions into my emergency distance learning work this spring, and got some very thoughtful responses:

I’ve been trying to encourage my students to go beyond re-reading notes and memorizing algorithms for years, with varying levels of success. The Power Tools give me a framework for helping my students become “fluent” in the math skills we’ve learned.

Fortunately, Agarwal and Bain anticipate that teachers will need student (and parent, and admin) buy-in to make the Power Tools really pay off in class. So they wrote an entire chapter titled “Spark Conversations With Students About The Science Of Learning”. It includes six steps to starting that discussion:

- Empower Students By Sparking A Conversation

- Empower Students By Modeling Power Tools

- Empower Students By Fostering An Understanding Of Why Power Tools Work

- Empower Students To Harness Power Tools Inside The Classroom

- Empower Students To Harness Power Tools Inside The Classroom

- Empower Students To Plan, Implement, And Reflect On Their Power Tools

These are tough conversations, and necessary conversations. Old habits (of study and of “doing school”) are hard to break. Asking students to intentionally think about and name what they know and what they don’t know is challenging. Breaking away from the “photomath” mindset pushes students out of their comfort zone. Teachers too, if I’m gonna be honest.

I recall a moment early this past school year when a student (who I knew was really really successful grade-wise in her algebra class) looked at me for help on a quadratic equation problem that showed up in a skills review in my geometry class. She literally said “I have no idea what to do with this”. I’ll admit that deep down inside I was a little judgey. Like, “what do you mean you don’t know how to solve a quadratic equation? It was only four months ago and it was literally one of the most important skills in the whole course!” Quickly I caught myself and remembered that a lot of things we learn one time evaporate over a summer. Otherwise, why were we reviewing skills? So we sat together and I nudged her to factor the quadratic first and things fell into place.

But this is where retrieval practice and “judgements of learning” come into play. From Day One, if we are constantly thinking about what we know and what we don’t know, reaching back intentionally to recall prior learning, giving students low-stakes opportunities to test themselves before an assessment, giving them actionable feedback, we give our students the tools to learn for the long term.

When we return to school the learning loss from an extended period away from an in-person setting is going to be only one of many challenges we’ll face. Regardless of what school looks like in August, the tools I read about in Powerful Teaching can help my students organize their knowledge, prioritize their time for study, and power through the most challenging school year any of us have ever faced.